Can you believe it—it’s been 84 years since the plane carrying Carole Lombard and 21 others smacked into the cliffs atop Mt. Potosi, Nevada, 35 miles southwest of Las Vegas. I’ve spoken often about the climb I made to the crash site in 2012 over the route taken by first responders (I did it in October; they did it in a foot of January snow), as I’ve related how I heard—as in, actually heard—the people on the plane whispering to me while I was there: “Don’t forget about us.” That experience led me to track down the story of each of the 21 souls aboard TWA Flight 3 along with Lombard.

But today let’s focus on the former Paramount starlet turned free agent performer and American patriot who undertook a perilous trip from warm and secure Los Angeles to snowy Indianapolis via Chicago in deepest winter to sell war bonds. Remember, America had just been sucked into World War II six weeks earlier and she was first among Hollywood stars to hit the road for fundraising. She was a passionate woman in everything she did, which she said herself. In whatever pursuit, according to Carole, “I give it my all and I love it.” That same passion would kill her, ironically enough. She didn’t have the patience to take three days to return to LA by train after the big success of the bond sale, and so she demanded to fly home. Her handler for the trip, MGM publicity man Otto Winkler, secured three tickets to Burbank (Carole’s mother Elizabeth Knight Peters also along) on a TWA cross-country flight that hedge-hopped from LaGuardia west. They picked the plane up in Indianapolis early on January 16 and spent the next 12 hours flying, getting off the plane, stretching legs, and getting back on again. We’re not talking about an Airbus here; the cabin of a DC-3 was about as big as the interior of a mass transit bus, meaning everyone spent the trip uncomfortable and very cold despite cabin heaters. Oh, and deaf thanks to two big radial engines droning away three feet outside the fuselage.

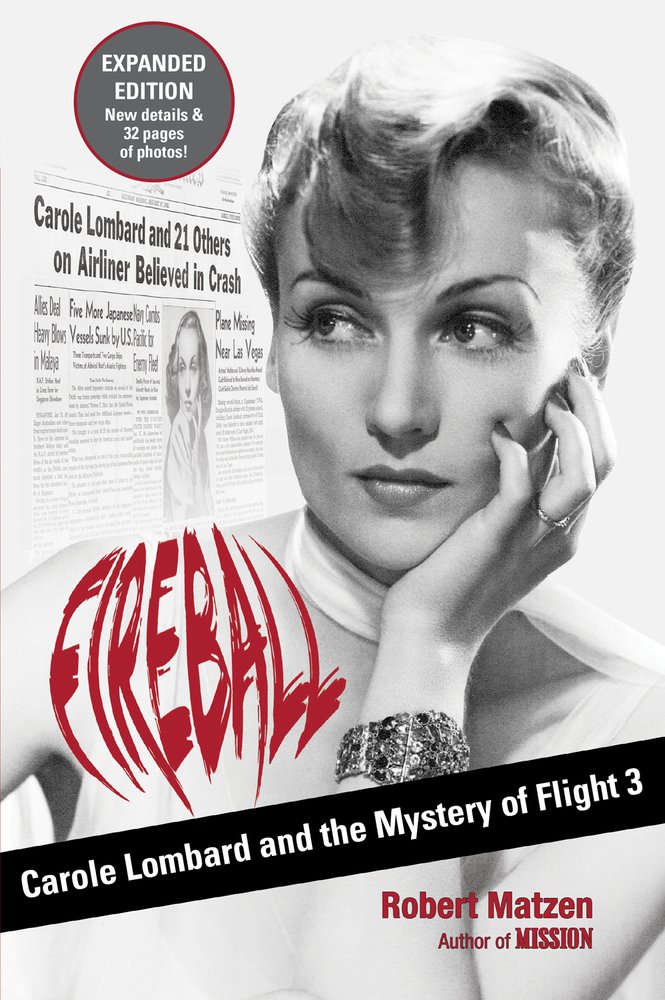

As documented in my 2014 book Fireball, the plane hit the mountain at about 7:30 p.m. local time on January 16. Initially rescue teams scrambled up the mountain hoping for survivors, but there weren’t any—although a few of the passengers had been tossed out of the plane into deep snow and may have lived past impact, if briefly. Carole was near the front of the plane and was found at the base of the cliff, under a wing.

For Carole, time stopped at age 33, and I’ve often pondered what would have come next if she had lived. Her career was on a downswing, although the picture she had just made, To Be or Not to Be, was a brilliant sendup of life in Poland under Hitler. Hard to say if the world was ready to laugh at the evil one in great enough numbers to make the picture a hit, but it stands today as one of her three best films. After that, she was set to make a sequel of sorts to her 1936 screwball comedy, My Man Godfrey. It was to be called “My Girl Godfrey,” with Carole the butler this time. And then, who knows where she would have gone.

Here are my suspicions. I believe she would have been the one to blaze the trail that Lucille Ball established (neither Carole nor Lucy being singer/dancers). Some comedies, some film noir, and then, television with a capital T. Ball always credited Lombard as her mentor; Lucy said that Carole appeared in her dreams offering career-altering advice. I don’t put that past Lombard at all; she didn’t have the opportunity to master the new medium, so she did the next best thing.

Lombard was an OK dramatic actress but excelled at comedy. She was so naturally funny, with great timing, that success on the small screen would have been inevitable for Carole in her middle years given the prevalence of star-driven TV series of the 1950s. Loretta Young, Donna Reed, Gale Storm, etc. etc. Pushing back against that success might have been declining beauty, a la Paulette Goddard and Ann Sheridan, both heavy smokers. Sheridan grew so alarmed at her fading looks by the late 1950s that she resorted to cosmetic surgery and then resurfaced in the 1960s TV series Pistols N Petticoats before dying suddenly of lung cancer. And that was another risk for a heavy smoker, which Carole had been since adolescence.

If she truly had gone the debauched way of, say, Talullah Bankhead, she could have slipped behind the camera as did Ida Lupino to direct features or television. She was whip-smart at the business end of Hollywood—witness the fact that in 1937 she was the highest-paid star in town without a resume to back it up.

I like to think, looking back on this anniversary, that Carole Lombard had another 40 years in her at least as a triple threat—actor/director/producer. Unfortunately, she gambled it all on the flip of a coin and lost. No, really, she flipped Winkler for it, heads the plane, tails the train. Let that be a lesson to all of us: There are consequences when you least expect them. If only you had taken that train, Carole, so that we could all have enjoyed six or eight seasons of The Carole Lombard Show, which would still be running today on MeTV.

Fireball: Carole Lombard and the Mystery of Flight 3 is available at bookshop.org, barnesandnoble.com, and Amazon.com. The audiobook was read by the incomparable, award-winning Tavia Gilbert.