I watched the 1952 version of Ivanhoe last night. It’s the first time I really consumed Ivanhoe because I will now admit, I’m not a big MGM guy or a big Robert Taylor guy, so I have seen bits and pieces of Ivanhoe over the years but never sat down and watched it until last night. And what I saw was good and then almost-great.

What really became a thing for me as I watched was realizing that Ivanhoe was a sort of remake of Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood a mere 14 years—and a world war—later. In that regard, Ivanhoe is a more adult, grittier picture presented to audiences now grounded in darker cinematic themes. But there are many similarities between the pictures in that both main characters face the same time period with only slightly different points of view. Robin of Locksley’s POV as a Saxon nobleman is replaced by Wilfrid of Ivanhoe’s as another Saxon nobleman, and they share the same plot: the Normans under Prince John are in power in England because King Richard is being held prisoner for ransom by the Austrians. Combating the bigotry and injustice of the Normans is an outlaw named Robin Hood who has an army of Saxon guerrilla fighters in the forest who are determined to end the oppression of the French invaders. Robin Hood, or “Locksley” as he is known here as played by British actor Harold Warrender, is a prominent character in the screen version of Ivanhoe as he was in Sir Walter Scott’s source novel, and Locksley’s band works in coordination with Wilfrid of Ivanhoe to bring down Prince John. Spoiler alert: just as in The Adventures of Robin Hood, a regal King Richard appears at the last minute to stare down his slimy brother, end the Norman reign, and declare that great things are ahead for England. We had seen Richard briefly in reel one, imprisoned all alone in an Austrian castle, which makes his appearance at the end with 100 immaculately and identically costumed knights really stupid. It’s like they were supposed to report to another movie and got sent to the wrong location.

The storybook way Richard rides in to bring the narrative to a swift conclusion works against every gritty moment that came before in Ivanhoe. It’s way too pretty and way too pat and much more like something out of the pre-war Flynn picture.

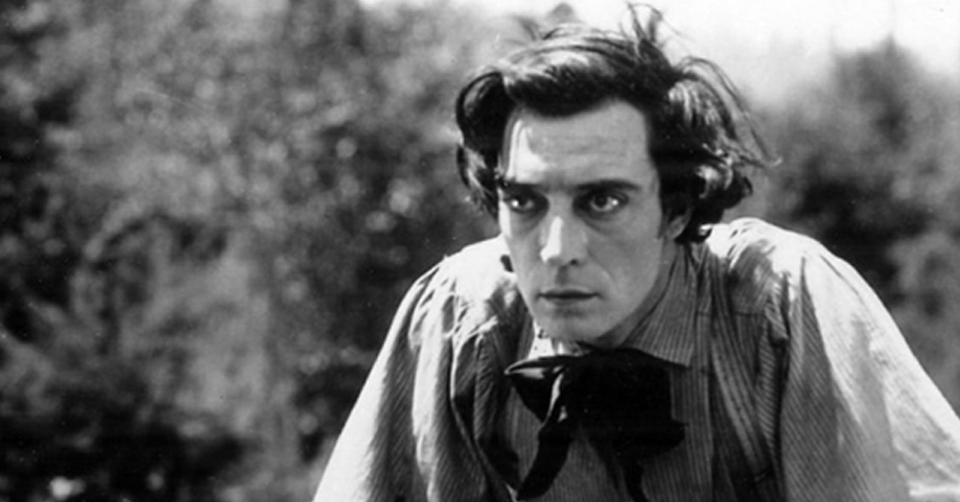

As much as I love the Flynn version and the way he built a winning team—an invincible winning team—he was so damn competent that the outcome was never really in doubt. Robert Taylor’s older and more weathered Ivanhoe, on the other hand, wins a lot but loses sometimes and when he loses, he bleeds. Up to the final confrontation, you feel like this is a real dude doing real things.

Just to ruffle feathers, I’m going to state a personal preference for George Sanders’ Sir Brian de Bois Guilbert over Basil Rathbone’s Sir Guy of Gisbourne as a villain. As laid out in Robin Hood, Sir Guy kept saying, “I’m gonna get that Robin Hood.” “I’m gonna hang that Robin Hood.” “That Robin Hood is in sooooooo much trouble!” but we never got a sense that Errol Flynn was really in trouble because he won every battle large and small except for the time he was bored and wanted to be caught so he could escape to piss Sir Guy off. Robin Hood’s wits and athleticism rendered Sir Guy into a villain who was all bark and no bite. But Sanders’ Sir Brian de Bois Guilbert is a brawny, earthy villain with a realistic perspective and a palpable lust for the “Jewess” Rebecca, played by Elizabeth Taylor. Where Rathbone’s Sir Guy had a glancing crush on Maid Marian—something more alluded to than depicted—Sanders is like, I want this girl and she’ll do whatever I say this instant! And I mean, whatever I say! His was a dark, domineering corruption of courtly love well past anything dreamed of by Sir Guy of Gisbourne.

Then there is de Bois Guilbert’s fellow Norman knight, Sir Hugh de Bracy, played by a Robert Douglas who seemed to get off on this type of character—he played basically the same snarling evildoer in Adventures of Don Juan just four years earlier. What a pair Sanders and Douglas make as foes for Wilfrid of Ivanhoe! You just don’t know what these two will do next, except it’s probably going to be lethal.

The Adventures of Robin Hood was conceived as a fantasy with sequins and tights, and you never really lost the feeling this was a comic book shot in Hollywood USA. I’ll go a step further and say you could watch the 1938 Flynn Robin Hood with today’s series of Marvel pictures and see Sir Robin as another gravity-defying superhero. Wilfred of Ivanhoe, not so much. There is literal and figurative gravity in everything about the setup of the story and the action driving it. There are bitter interpersonal conflicts, and the oppression of the Saxons by the Normans isn’t depicted through a few token outrages—it permeates the people and times. Check out the Ivanhoe trailer.

In Ivanhoe, there are two women love interests for our hero, creating a triangle, whereas for Flynn’s Robin Hood there was only Maid Marian. It’s interesting to me that MGM cast in the Marian/female lead role Olivia de Havilland’s sister and bitter rival Joan Fontaine, years older at 34 than Livvie was at 21, but sporting similar braids and looking almost creepily alike, although the interpretations of the actresses were quite divergent. Livvie’s Marian was warm, charming, and ingenuous while Joanie’s Rowena was typical of this actress—pretty but aloof, distant, and at times unengaged. Then there was Elizabeth Taylor’s Rebecca, way younger and more passionate and ready at any moment for Ivanhoe to carry her off to destinations unknown. Whatever he wanted was OK by her.

As conceived in 1937 at Warner Bros., Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood was to open with a grand jousting tournament that established the enmity of Sir Robin and Sir Guy, but for budgetary reasons this sequence was cut from the production. Ivanhoe gives us not one but two jousting sequences, one a full-scale, thrilling set of jousts with Ivanhoe unseating Norman knights bang, bang, bang, one after another. They look painfully authentic because they were, thanks to location work in England and historical accuracy provided by the British Museum. We feel the grounding of this picture in medieval times because it was shot entirely in England with the supporting players cast there and real castles used along with a modern fortress replica constructed just for the production.

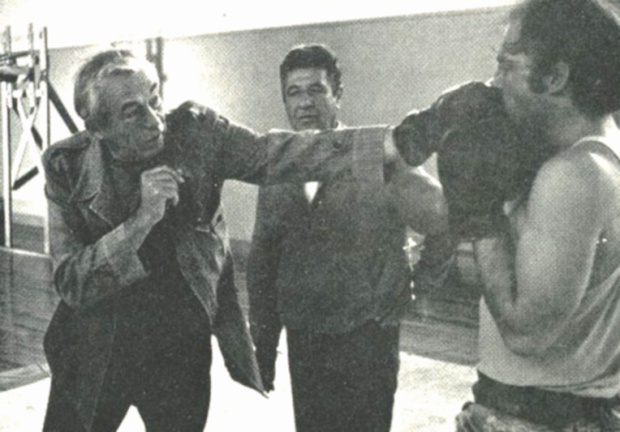

The combat depicted in Ivanhoe is raw in its brutality, up to and including the final confrontation between Sir Wilfrid and Sir Brian. Just, ouch. In The Adventures of Robin Hood, a single feint and sword thrust dispatched Sir Guy after a lengthy, well-choreographed duel. In Ivanhoe, Sir Brian dies hard after many minutes of lance, ax, and chain-and-ball attacks. It’s a vicious conclusion and praise must go to George Sanders for whipping up surprising sympathy in his final moment as he declares his love to Rebecca and then expires. And up until the very last few feet of run time, we don’t know if Ivanhoe is going to choose distant, aloof Rowena or hot young Jewess Rebecca. OK, I will leave one outcome in Ivanhoe unspoiled. You’ll have to see for yourself.