Presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin is my hero. She and I have shared the stage twice, the first time 20 years ago in Presidents Day interviews on KDKA Radio Pittsburgh talking about George Washington, and then more recently in a joint interview with Joe Scarborough, Mika Brzezinski, and Willie Geist on MSNBC’s Morning Joe discussing the holiday tradition of It’s a Wonderful Life and the circumstances of its creation just after World War II. Recently I saw Doris on C-Span as she donated the DKG and Richard Goodwin papers to the University of Texas at Austin Library. Doris said something to the effect that “it breaks my heart” that so few people are studying history these days. It breaks mine, too. And it probably breaks yours, because if you read my columns you are, de facto, a history-lover.

History’s my thing. I’d much rather retrace old footsteps than blaze a trail of my own. When I go to Gettysburg, I hear the guns. When I visit Warner Bros., they’re making The Adventures of Robin Hood and Casablanca. On a street here in my hometown, I fixate on the spot where the Flathead Gang blew up an armored car in 1927. If you don’t get history, my friend, you can rest assured that I won’t get you.

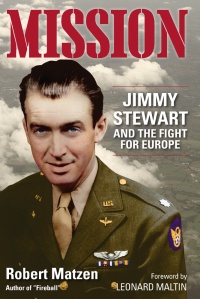

Recently I was invited to appear on a holiday edition of History Camp, an hour-long video interview series, discussing Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe and the circumstances around the making of It’s a Wonderful Life. This show will air Thursday, December 22, at 8 p.m. ET.

It’s an understatement to say that I admire the work of this nonprofit, The Pursuit of History, which stages on-location workshops at historic sites in Boston, Philadelphia, and other places, and provides virtual events, including its weekly author interview series. A quote on their website states, “We create and present these innovative programs because we believe that more people gaining a broader understanding of history has never been more important.” I share this belief, that the accumulated knowledge and wisdom provided by history can guide us in uncertain times—like now. I encourage you to sign up for their emails, donate to the cause, and begin walking in historic footsteps. Pursue history with this group, from the Egypt of Tutankhamun to Radio City Music Hall, from Valley Forge to Camp David. These people believe in preserving the past, just as I believe, and you probably believe. It’s common sense that those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. But learning about history is also Fun with a capital F. The best stories are the true stories, crazy twists of fate, people defying odds, and outcomes that changed the future of individuals and nations. Come on, take my hand. Let’s jump through the portal and revisit the past in The Pursuit of History.

Happy Holidays, everyone.

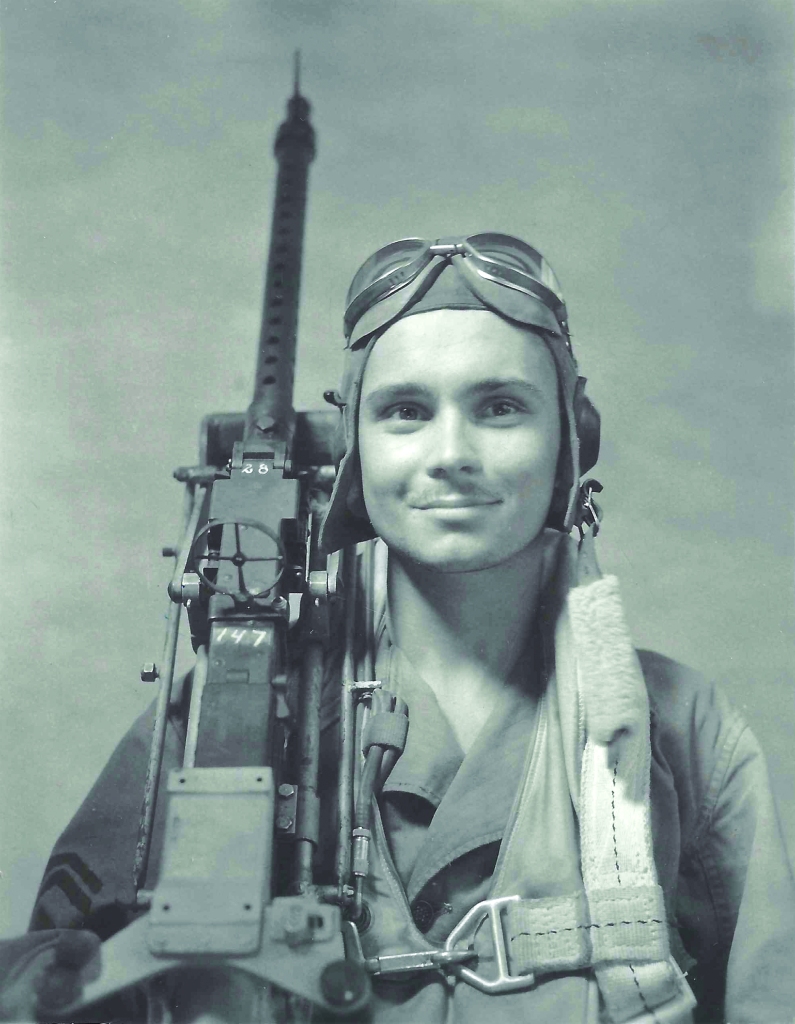

Hollywood’s beloved boy-next-door movie star Jimmy Stewart was one of those draftees and had entered the service in February 1941. As described in my book Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, he was, as of Dec. 7, Corporal James Stewart, and in less that a month he would earn his wings as an Army flier with the rank of second lieutenant. (If you’re a WWII history lover, please explore this

Hollywood’s beloved boy-next-door movie star Jimmy Stewart was one of those draftees and had entered the service in February 1941. As described in my book Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, he was, as of Dec. 7, Corporal James Stewart, and in less that a month he would earn his wings as an Army flier with the rank of second lieutenant. (If you’re a WWII history lover, please explore this