If you want to understand It’s a Wonderful Life, watch the 1949 20thCentury-Fox production of Twelve O’Clock High. Then sit there, digest what you’ve seen, and watch it again. Twelve O’Clock High has been recognized as the most accurate depiction of life in the Eighth Air Force, as proven by the fact it became required viewing at U. S. service academies in the 1950s.

The war depicted in Twelve O’Clock High was Jim Stewart’s war, marked by Quonset huts, mounting pressure, mud, and boring routine punctuated every so often by terror at 20,000 feet and the sudden death of your roommate.

Before D-Day in June 1944 the only Americans fighting in Northern Europe flew for the Army Air Forces and Jim was one of those guys, not in the first wave of bombers over Europe but in the second that came up as reinforcements. The first wave can be seen in Twelve O’Clock High, flying missions from southeastern England over the Channel to the coast of France, which in mid-1943 was dangerous and highly defended German territory as proven by the losses and stress on a bomb group that Gen. Frank Savage has to bring back to life through discipline. The story was written by veteran Hollywood screenwriter Sy Bartlett and former bomber pilot and journalist Beirne Lay, Jr., both of whom served in Eighth Air Force Bomber Command during the war—served, in fact, in close proximity to Captain, then Major, James Stewart of the 445thBomb Group.

I have found no record whether Jim saw this picture or if he avoided it, which he might well have because of his close personal connection to events depicted. Right after the war Beirne Lay had written a two-part Saturday Evening Post exposé on Jim’s military service; had in fact written it from the inside, from knowing Jim during his 20 months in-theater. Jim would have remembered too well, from too close a proximity the life depicted in Twelve O’Clock High—those claustrophobic half-moon Nissen huts and the bad overhead pendant lighting, Franklin stoves that never alleviated the damp and cold, relentless English rains, all-night mechanical sessions to get ships that had been shot to pieces one day airworthy for the next, and the black curtain that opened to reveal not only the day’s target but also the place where some of the men being briefed were going to die. He’d have known the terms that are never explained, the I.P. (initial point of the bomb run) and the D.P.I. (desired point of impact of the bombs). He’d have recognized the boyish face of Lieutenant Bishop because Jim had known a hundred Lieutenant Bishops. And Jim would have known the feeling when Bishop is lost in combat because, as a squadron commander, Jim lost pilots and had to live with any error in judgment that had led to their deaths.

Like General Savage, played by Gregory Peck, Maj. Jim Stewart believed in group integrity, which was a disciplined approach to formation flying that maximized machine gun coverage from each ship’s ten machine guns and raised the odds of actually hitting any target. All the men I talked to who served under Stewart said he was a “by-the-book officer” both on the ground and in the air. As the decades passed, many apocryphal stories brewed up from men who said they had served under Stewart and described hapless Jimmy with the slow aw-shucks drawl who looked the other way from infractions. Don’t believe it. You don’t rise to the rank of full colonel in the USAAF and brigadier general in the Air Force Reserve by being a friend to enlisted men. Jim Stewart was tough.

I’ll touch just a moment on the Twelve O’Clock High production, with bases in Alabama and Florida standing in for Archbury, England. By my count they could muster eight stateside B-17s to represent a bomb group’s IRL complement of about fifty. Even a few years after the war they were being scrapped at a high rate. Please note as you watch the picture director Henry King’s use of long, unbroken takes under those stark pendants. I counted one scene between Gregory Peck and Hugh Marlowe as the “coward” Colonel Gately that ran more than five mesmerizing minutes, just the two of them in a scene of complex dialogue to match anything from The Caine Mutiny. One take! And it happens several times with Peck and his cast, the camera rolling and rolling on a two-shot, swooping in, moving back, but never a break. Everything they discuss, every issue they face, was based on what Bartlett and Lay saw during the war. Savage is really Col. Frank Armstrong and Maj.-Gen. Pritchard, played by Millard Mitchell, is really Maj.-Gen. Ira Eaker, first in command of the fledgling Mighty Eighth. Down to the sergeant who needs a zipper on his stripes because they keep getting put on and taken off, the characters are based in fact. The issues were just as real, as when Dean Jagger as Ground Exec Stovall gets drunk and says he can’t remember anyone’s face who has died in combat except they were all “very young faces,” or when Paul Stewart, the group’s doc, likens these young men to light bulb filaments burning bright one minute and burning out the next.

The parallels to Stewart’s war keep coming in this picture. Tough-as-nails Savage finally cracks after seeing the pilot he had counted on most die in the air. When you see Peck come apart right there on the perimeter track, think of Jim because the same thing happened to him. The exact same thing. He returned from somewhere around his twelfth mission and his plane cracked in two on landing, and Jim cracked with it. He went “flak happy” and had to go away to recover in the English countryside. It happened to many of the fliers; in fact, early in the film a navigator commits suicide after fouling up and that happened quite a lot as well—men blowing their brains out with their .45s because they couldn’t take it anymore.

Twelve O’Clock High only misses on a couple of things and both are understandable. The cast is simply too old. The officers who flew the missions at the front of the plane were in reality 20 at the youngest and 26 at the oldest, while in the picture the primary fliers were relatively ancient: Hugh Marlowe at 38, Gary Merrill 33, and John Kellogg 32. Robert Patten at 25 looked the part and was in fact the only actor in the cast with Eighth Air Force experience, serving as a navigator. The other miss is high-altitude flight as represented by the combat sequence that takes place an hour and a half into the picture. Yes, the cockpit crews are on oxygen and in helmets and goggles, but you never get the sense of life below zero degrees at 20,000 feet. It’s something Hollywood has never managed to capture and probably never will, but it’s another key to understanding the PTSD of those men on the front lines in 1943 Europe.

Twelve O’Clock High and It’s a Wonderful Life ought to be a double feature, and it doesn’t matter which you show first. When Jim Stewart came back to become George Bailey, he had just left the world of General Savage behind. He had lived in that base with those men in the same conditions under the same stress flying the same missions, and he too had cracked under the strain. The adult children of these fliers tell of a certain distance, sadness, and blind rage that could be experienced from “Pop” at any moment, and Twelve O’Clock High explains it all. Jim’s kids will tell you the same thing, that the war must have changed him because of that distance, sadness, and occasional blind rage.

When I see Jim first appear in It’s a Wonderful Life as an adult, when the camera freezes and his arms are wide and he’s supposed to be playing a young guy of 21, I squirm because I see an old man and the face of war. A hairpiece and makeup can’t hide the horrors he had just encountered, which is why Twelve O’Clock High should be mandatory viewing for anyone who loves It’s a Wonderful Life. It’s the prequel that tells the story of an actor’s redemption and remarkable return to peacetime.

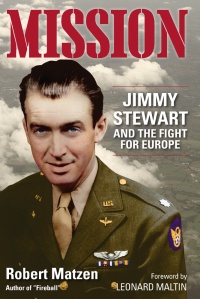

Hollywood’s beloved boy-next-door movie star Jimmy Stewart was one of those draftees and had entered the service in February 1941. As described in my book Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, he was, as of Dec. 7, Corporal James Stewart, and in less that a month he would earn his wings as an Army flier with the rank of second lieutenant. (If you’re a WWII history lover, please explore this

Hollywood’s beloved boy-next-door movie star Jimmy Stewart was one of those draftees and had entered the service in February 1941. As described in my book Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, he was, as of Dec. 7, Corporal James Stewart, and in less that a month he would earn his wings as an Army flier with the rank of second lieutenant. (If you’re a WWII history lover, please explore this