When you hear the name Audrey Hepburn, what films come to mind? Quick! Don’t sit and think about it—rattle them off. Breakfast at Tiffany’s, right? Sabrina? Roman Holiday? Then what? Charade, the pretty good homage to Hitchcock? My Fair Lady, although that’s so much less an Audrey picture and more a Broadway musical. She made so few pictures, so shockingly few, and there was seemingly no rhyme or reason to what she agreed to star in. How does this girl go from Sabrina to War and Peace? Then to Love in the Afternoon as the romantic interest for a man twice her age who looks three times her age. Then to a weirdo picture like Green Mansions and an unexpectedly deep The Nun’s Story, followed by the depressing western The Unforgiven. And then, after the offbeat Breakfast at Tiffany’s, she makes the masochistic (for all involved) Children’s Hour. I’m whiplashed! Sorry, Audrey, but, I just don’t understand what your agent was thinking. If I had to guess, I’d smell a rat named Mel Ferrer (Audrey’s hubby), who never met a decision he couldn’t screw up.

Granted, Audrey came along at absolutely the wrong time to become a Hollywood star, in the early 1950s when television delivered unrelenting body blows to the motion picture industry. Hollywood had been humming right along through the war until infected by the small screen, the boob tube, the vast wasteland. Suddenly everything looked like Monogram or Republic or PRC in terms of production values as Hollywood was churning out 39 episodes of TV junk a season. All of which left the stars scrambling to find big-screen releases worth making. Suddenly it was a crazy game of musical chairs where the stars went from the luxury of 300 chairs in 1946 to 30 chairs by 1956, which left many falling on their asses.

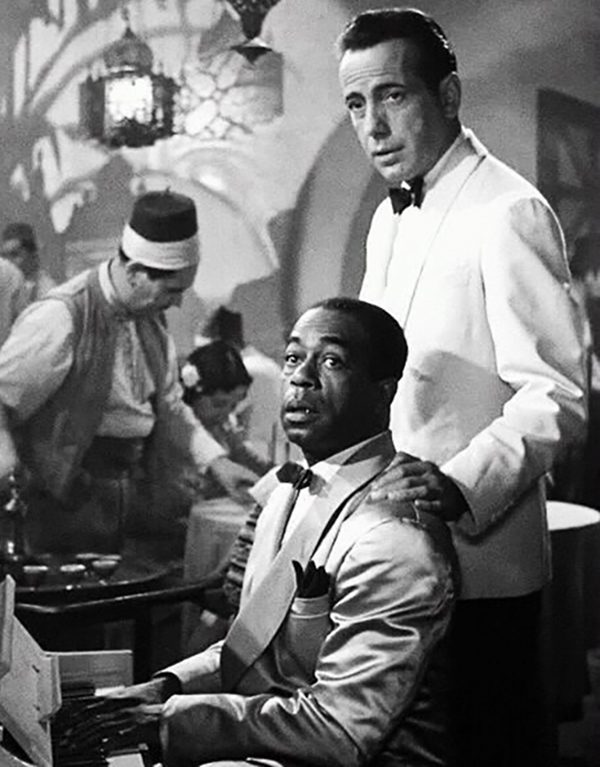

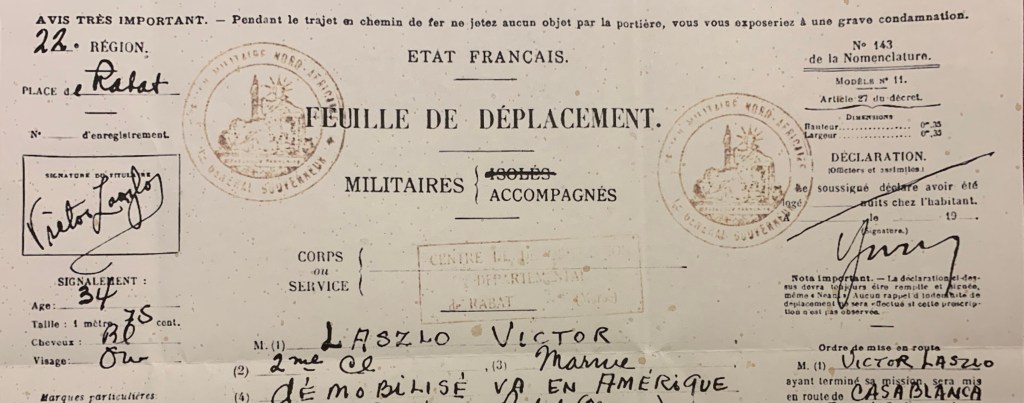

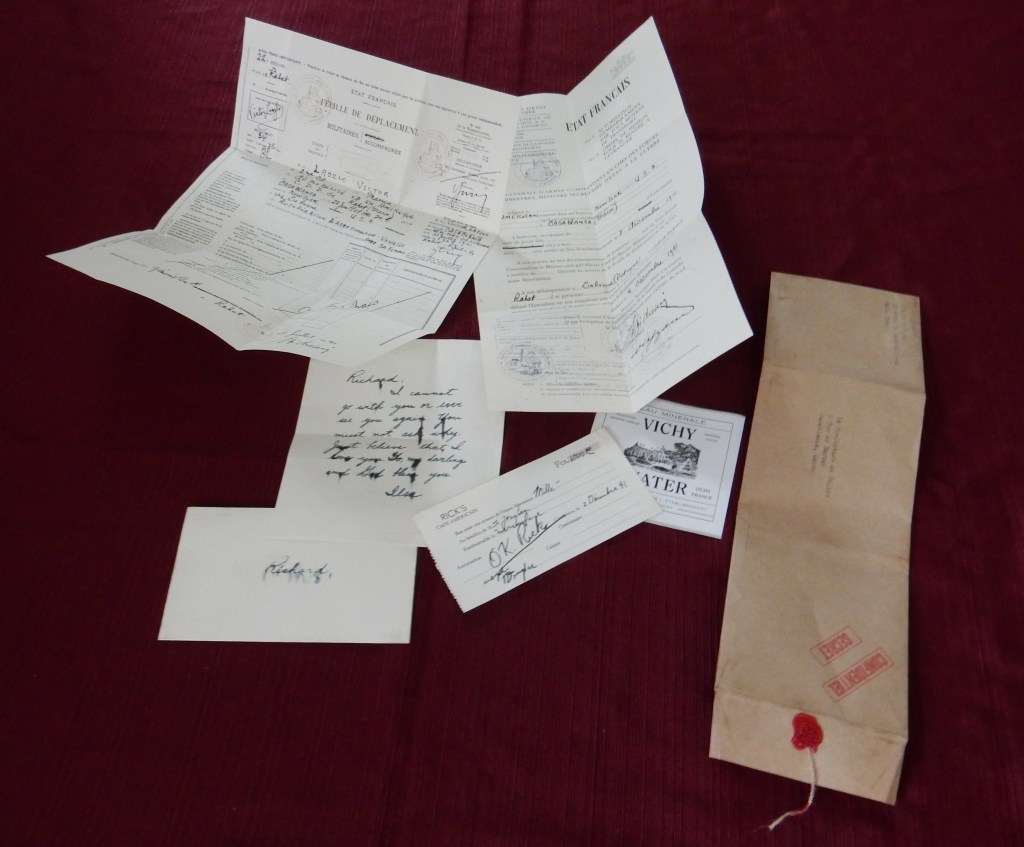

That’s your backdrop, which makes Audrey’s 1966 feature, How to Steal a Million, such a treasure. Granted, for me, it’s a personal crossroads since I wrote two books about Audrey, and I get excited to see Fernand Gravet, who appeared in my book Fireball about Carole Lombard, and Marcel Dalio, who appeared in my book Season of the Gods about the making of Casablanca, and Hugh Griffith, who would later appear in Start the Revolution Without Me, a crazy sendup of my favorite author, Alexander Dumas. And the whole thing takes place in Paris, one of my favorite cities. For me, How to Steal a Million is like Ralph Edwards popping in to shout, “Robert Matzen, This Is Your life!”

Why is it exactly that How to Steal a Million isn’t mentioned in anyone’s first breath when asked about a favorite Audrey Hepburn picture? I don’t understand it. On the Dutch Girl book tour, I was asked a dozen or more times to name my favorite Audrey movie and of course there’s Roman Holiday, but How to Steal a Million is right up there beside it. Both were directed by William Wyler, Audrey’s favorite taskmaster. Truth be told, she was a moth to flame when it came to domineering men, both personally and professionally. None fit that bill in her personal life better than Ferrer, a brittle and insecure man that she shed herself of much later than she should have.

Professionally, she knew she needed a firm hand at the tiller because she didn’t believe in herself as an actress. She said so time and again. “I’m not an actress; I’m a dancer.” She talked down her acting skills so loudly and so often that it sounded like false modesty, but, believe me, in her case it wasn’t. She hadn’t sought an acting career; she hadn’t come from the stage. She began to accept walk-on movie parts in England in 1951 and 1952 because she needed to eat and she had a mother to support. It was never out of burning ambition. There was an inevitability about her screen success because she fit a type that Hollywood had been lacking and possessed unique qualities that have kept her at the forefront for 75 years and counting, more than 30 years past her death.

In Roman Holiday, you can’t see it in the final print, but she spent her time in Rome a duck out of water. William Wyler wrenched that performance out of—and created—Audrey Hepburn. She was clay; he molded the clay. “He discovered me and nurtured me,” said Audrey of Wyler. “He was very protective of me.” Thirteen years and 13 pictures later they reunited for How to Steal a Million, the story of Nicole, who hails from a line of art forgers. She must find a way to steal her grandfather’s knockoff of Cellini’s Venus from the Kléber-Lafayette Museum before it can be examined and proved a fake. Peter O’Toole plays Simon, her unlikely but highly competent confederate and love interest.

Watching these two in this story is like sitting down and eating an entire Whitman Sampler without worrying about getting fat. It’s a treat, it’s delicious, and you just let yourself go. The story is charming; the characters are charming; the actors are charming. Every exterior is spectacular because it’s Paris—Notre Dame, the Latin Quarter, the Seine, the Louvre, the Musée Carnavalet.

And that dialogue, just, Wow. Nicole mentions that she’s going on a date with a rich American art collector. Her father—an art forger like his father—says offhandedly that he had sold this American a Toulouse Lautrec painting. Alarmed, she says, “Your Lautrec or Lautrec’s Lautrec?” He replies, “Mine, naturally.” When she groans, he grows offended: “Are you implying that my Lautrec is in any way inferior?” Bug-eyed Hugh Griffith is such a grand actor and perfect as her father the forger.

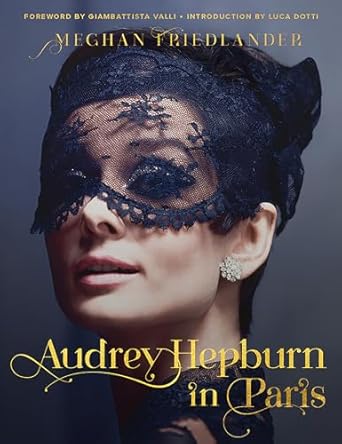

During the heist, Nicole is to dress as a scrubwoman, and when she asks why, Simon, her confederate, says dryly, “Well, for one thing, it gives Givenchy the night off.” Hubert de Givenchy, of course, being Audrey Hepburn’s designer of choice. In this picture, he created 24 outfits for her, none so spectacular as the black number with a black lace eye mask that’s featured on the cover of Meghan Friedlander’s excellent book, Audrey Hepburn in Paris (with an introduction by my pal Luca Dotti).

There are a few clinker moments in How to Steal a Million, some bits of business that fall flat, just a little here and there, like when you think you’re biting into a buttercream and it turns out to be lemon instead. These bits hint to me that Wyler wasn’t sure he was getting gold when time proves he was. Don’t cheapen the proceedings, Willy. Just create your masterpiece.

Word to the wise: Don’t get How to Steal a Million confused with a clinker of a picture Audrey had made three years earlier called Paris When It Sizzles. Yikes what a disaster that one was. When your leading man (William Holden) has been carrying a torch for you for 10 years and you’re married with an omnipresent husband, that’s bad. When the leading man shows up drunk to the set most days, requiring an eventual intervention, that’s worse. And Holden was just one of the problems plaguing production to the extent that Paramount Pictures hid the final cut in the vault for two years with the knowledge that when they were forced to kick it out of the nest and into the world, Paris was going to fizzle. And it did.