My friend Tom sent me a link the other day. He had found a six-minute YouTube video on the topic of a particular shot in the movie Casablanca and thought I would be interested in seeing it since my last book, Season of the Gods, told the day-by-day, way-behind-the-scenes story of the creative minds who got together and spun this 1942 cinematic masterpiece. The other reason Tom sent it to me is that he made a long, successful career as a film and video editor who taught me most of what I know about the craft, and the shot in question from Casablanca involved editing at its best—or rather, the shot represented a brilliant example of editing forbearance.

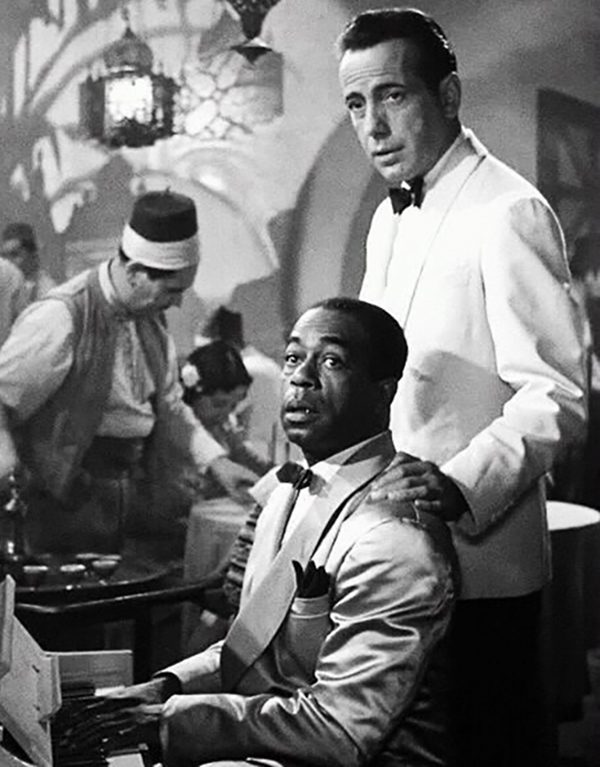

At plot point one in the picture, Rick sees Ilsa for the first time since Paris. Right before that encounter, Ilsa tells Sam the piano player that she wants to hear the song As Time Goes By. He starts to play, and she says, “Sing it, Sam.” As he starts to sing the song, the camera fixes on Ilsa’s reaction to hearing it. The last time I watched the picture, which I’ve seen many times, including on the big screen, the length of the shot struck me. It’s 25 seconds long, which is an eternity of screen time, particularly for a director like Michael Curtiz, who likes to keep things moving as he pushes his story forward, ever forward. But here, nothing happens in 25 seconds—and everything happens in 25 seconds.

The shot reveals that the past tortures Ilsa, but she must hear the song and dive headlong into her pain. As revelatory as the shot is, it’s also a director’s gamble since executive producer Hal Wallis might just notice the extraordinary length and fire off a memo to Curtiz to stop doing that! Or studio boss Jack Warner might send a memo along the same lines. Stop wasting film and money on these long takes!

As noted in the YouTube video, the shooting script of Casablanca didn’t mention a long, lingering close-up of Ilsa. The script simply shows Ilsa’s line, and describes Sam singing, and the stage direction has Rick walk in and see Ilsa. So, this was a Curtiz idea on the spot, and I can imagine how it came about. Cinematographer Arthur Edeson, a veteran of moviemaking going back 30 years and also a still photographer, had adjusted his lighting just right on Ingrid Bergman playing Ilsa. The setup caught a glint of light off her right eyeball and a glint of light off her left tear duct. They rehearsed the scene as written—she tells Sam to sing the song and Sam reluctantly complies. Edeson shot it over Bergman’s shoulder to Dooley Wilson as Sam, and over Dooley’s shoulder to her, and in a close-up of Bergman asking him to sing the song and then her reaction to it.

Here Curtiz or maybe Arthur Edeson noticed something special—Bergman’s inspired reaction to what she was hearing. Ingrid Bergman would create this great mythology later in life that she didn’t understand Casablanca or her character or whom she should be in love with—Victor Laszlo or Rick Blaine. But this shot reveals the big lie of all that nonsense. As crafted by director Curtiz, and shot by Edeson, and acted by Bergman, Ilsa knew exactly whom she loved. It’s written all over her face through 25 seconds. Ilsa loved Rick and Ilsa wasn’t over Rick.

Bergman had a remarkable ability to play it vulnerable her whole career, and in rehearsal Curtiz must have seen how powerfully Bergman was communicating a lost love, or Edeson perhaps noticed first, and director and cameraman would have conferred, and then for the close-up, I can hear Curtiz saying to her, “Think of something sad. Keep thinking about something sad.” He might have coached her through those 25 seconds knowing the song would be looped in separately.

Then I wonder what was her motivation; what was the sad thing she thought about? What came to mind was Ingrid Bergman’s recent exile in Rochester, New York, where she had spent an unhappy winter in deep snows waiting for the phone to ring with David O. Selznick at the other end of the line. Selznick owned her services at this time but kept not finding parts for her. So, the time dragged by for Bergman in snowy Rochester—3,000 miles from Hollywood—while her dentist husband progressed through a medical internship. She had gone into this period excited at the prospect of serving as a dutiful housewife, but then the reality hit her how out of place she was, how out of work she was, and the snow piled up, and letters to a friend revealed how deeply unhappy and then depressed she had grown during these months, feeling that Selznick had abandoned her, feeling she would never work again.

Whatever motivated her, the camera loved it and the director loved it, to the extent that this one shot would make it through Owen Marks’ editing booth intact at 25 seconds. Marks was an experienced hand with many Warner Bros. A-pictures under his belt, but he would not have made such a decision on his own. Curtiz must have fought for the length of this shot and Wallis must have OKed it, because 10 seconds would have been safer, 15 tops. But on it goes, uncomfortably so, until suddenly you realize you’ve strayed too deeply into Ilsa’s pain.

It’s one little gem in a treasure chest of a picture. It’s also an interesting decision by two or three or four of the gods in their season who came together to create a masterpiece.

__________

Season of the Gods is available in trade paperback through Barnes & Noble and Amazon.com. It’s also a dynamite audiobook read by Holly Adams.