Kasteel Zijpendaal tricked out as Nazi headquarters for the film Betrayed in 1954. It had indeed been taken over by German command in 1943 and must have looked pretty much just like this.

There was a high body count of Germans for the run of Betrayed. Here members of the beret-clad Dutch underground shoot their way out after rescuing Gable and take off.

One more, 2015 again, showing the side of the house scaled by “the Scarf” as he rescued Deventer. In real life, 11-year-old Audrey Hepburn loved to explore these grounds in 1941. She would read here on the lawn and play with the animals, which she preferred to people.

You could have knocked me over with a feather. I had a hankering to watch Betrayed the other night, Clark Gable’s last picture for MGM, made in 1954 and about the Dutch underground in WWII. I never much cared for later Gable pictures—he didn’t seem to care so why should I? But these days everything Dutch is important so there I was, watching Gable as Deventer, code-named “Rembrandt,” a Dutch CIA-type fighting the Nazis in his home country, which had been invaded and occupied by the Germans in May 1940. The first sequence in the picture was shot at Kasteel Zijpendaal—a locally famous Dutch castle built in the 18th century on a little lake at the edge of the city of Arnhem. It was “the ancestral home of the Baron van Heemstra,” Audrey Hepburn’s maternal grandfather who was once Arnhem’s mayor. As a girl of 10 and 11, shy Audrey communed with nature in the lush grounds surrounding the castle.

So there right in front of me was Kasteel Zijpendaal dressed up as Nazi headquarters, and there was Victor Mature as the notorious Dutch underground leader “the Scarf” rowing across the little lake and climbing in a window and helping Clark Gable to escape right before Deventer was about to be tortured and made to talk. There were fake hand grenade explosions inside, Germans mowed down by the machine guns of the Scarf and his men, and then Mature burst out the front door with Gable on his back, stole a Nazi staff car, and escaped. I was dumbfounded because Mary and I had been to this castle multiple times. The rest of the picture played out almost entirely in the Netherlands with Lana Turner parachuting onto Dutch soil as a spy planted by the Allies. She is in love with Gable but quickly gets mixed up with Mature amidst spy vs. spy shenanigans. And so on and so forth.

Something you don’t see every day: Lana Turner parachuting into hostile territory. To lessen your concern, I can report that she didn’t break a nail, let alone an ankle.

The depiction of Mature and the Dutch underground is hilarious. They were bumping off Nazis right and left in all these raids that never happened. At one point he and his men barge into a Luftwaffe base and annihilate a great number of Germans having a party. In truth, I love you dearly, Dutch people, but I terms of violence, you were only good at blowing off an occasional hand or foot—usually your own. When you outwitted a German, which you did all the time, it was by making an illegal radio the size of a matchbook or sending your kids out to steal dinner from the soldiers or hiding forbidden leaflets in the fake tummy of a fake pregnant lady. That was the way you won the war. One woman told me that when she was a little girl, a German officer came to their house and while he was in another room, she picked up his hat and spat in it. Classic Dutch mischief.

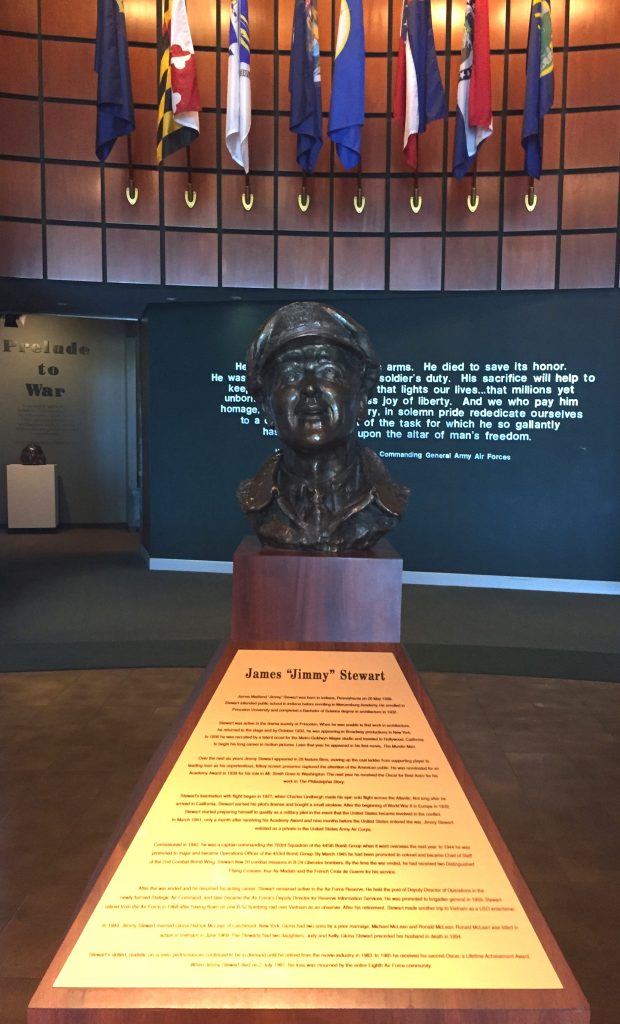

But they also did deadly serious stuff, like hiding thousands of Jews just before they would have been sent to Auschwitz, along with American and British fliers who fell from the skies after their bombers and fighters were shot down. One of these was Clem Leone, a friend of mine whose incredible story is chronicled in Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe. Thanks to many courageous Dutch people across the country, Clem evaded capture for four months as he made his way south through the Netherlands–it was a lousy Belgian that turned him over to the Nazis in Antwerp.

I did some reading in Lyn Tornabene’s Long Live the King and Jean Garceau’s Dear Mr. G. after finishing my viewing of Betrayed. Gable spent a month in the Netherlands shooting at various locations and was treated like his royal self everywhere he went. He was mobbed and it made all the Dutch newspapers. The location work was fantastic and everything you’d expect—lots of windmills, and dikes, and water, water everywhere. You just can’t replicate that stuff on a soundstage, and the lushness of the production, in Eastman Color no less, really surprised me given the dire straits of MGM at that time—TV drowning the studio’s books in red ink and most of its stars cut loose as a result. ‘Mr. G.’ went freelance at the end of production and never again walked through the gates of the studio that made him famous over the course of more than 20 years.

The ingenious payoff to the plot of the picture is that Gable provides information allowing 3,000 besieged British Airborne paratroopers to escape after the September 1944 “Bridge Too Far” battle of Arnhem. The title Betrayed refers to one of the three leads leaking the plans for Operation Market Garden to the Germans, which causes them to roll in two panzer divisions in anticipation of the Allies dropping 10,000 paratroopers behind Nazi lines to capture the Arnhem Road Bridge. The whole thing was a real-life disaster for the British and 7,000 of their boys ended up dead, wounded, or captured. The very last shot in the picture shows the Airborne survivors limping out of the fog after they had crossed the Rhine along an escape route mapped by heroes Gable and Turner.

If you know the history of this battle, the plot of Betrayed is a perfect fictional backstory that fits hand in glove with real-life events. Another surprise is that there’s very little explanation for what’s going on, meaning that Hollywood expected everyone in the 1954 audience to have the facts of Market Garden top of mind. It’s a level of sophistication that would never be anticipated by movie producers today.

I had no idea I was going to get to go back to Holland on a frozen Friday night in Pennsylvania and watch my Dutch friends do a whole bunch of crazy-heroic stuff to a whole bunch of hapless Germans. Oh, the Dutch were heroic in World War II all right. Much more heroic than simply wielding a machine gun. Come to think of it, Clark Gable had Dutch roots and his character in Betrayed is very Dutch indeed. He’s not a gun toter; he uses his brains at every step to outwit the thugs who hijacked the 20th century on their way to a thousand-year Reich. “Not on my watch,” was the response of the crafty, and ultimately liberated, Dutch.